BOTANICAL GARDENS AND COLONIALISM

Today, botanical gardens are presented as serene sites for appreciating plants from around the globe. Many of the same botanical gardens that celebrate “exotic” plants, as well as promote ecology and preservation, played a part in stripping the world of its biodiversity and resources.

European botanical gardens once served as laboratories and distribution centers for colonial powers. Colonial botanists would collect, smuggle, and steal plant specimens from distant lands to bring them back to these gardens for study. By identifying how to hybridize, cultivate, and harvest lucrative plants, botanists supplied world empires with even more ways to profit off their plunder. This is the birth of cash-crops and the plantation industry.

SPECIMENS AND COLLECTIONS

“Empire requires that scientists and their patrons share the belief that the stuff of nature can be captured in words, figures, lines, shading, gradients, or flows…”

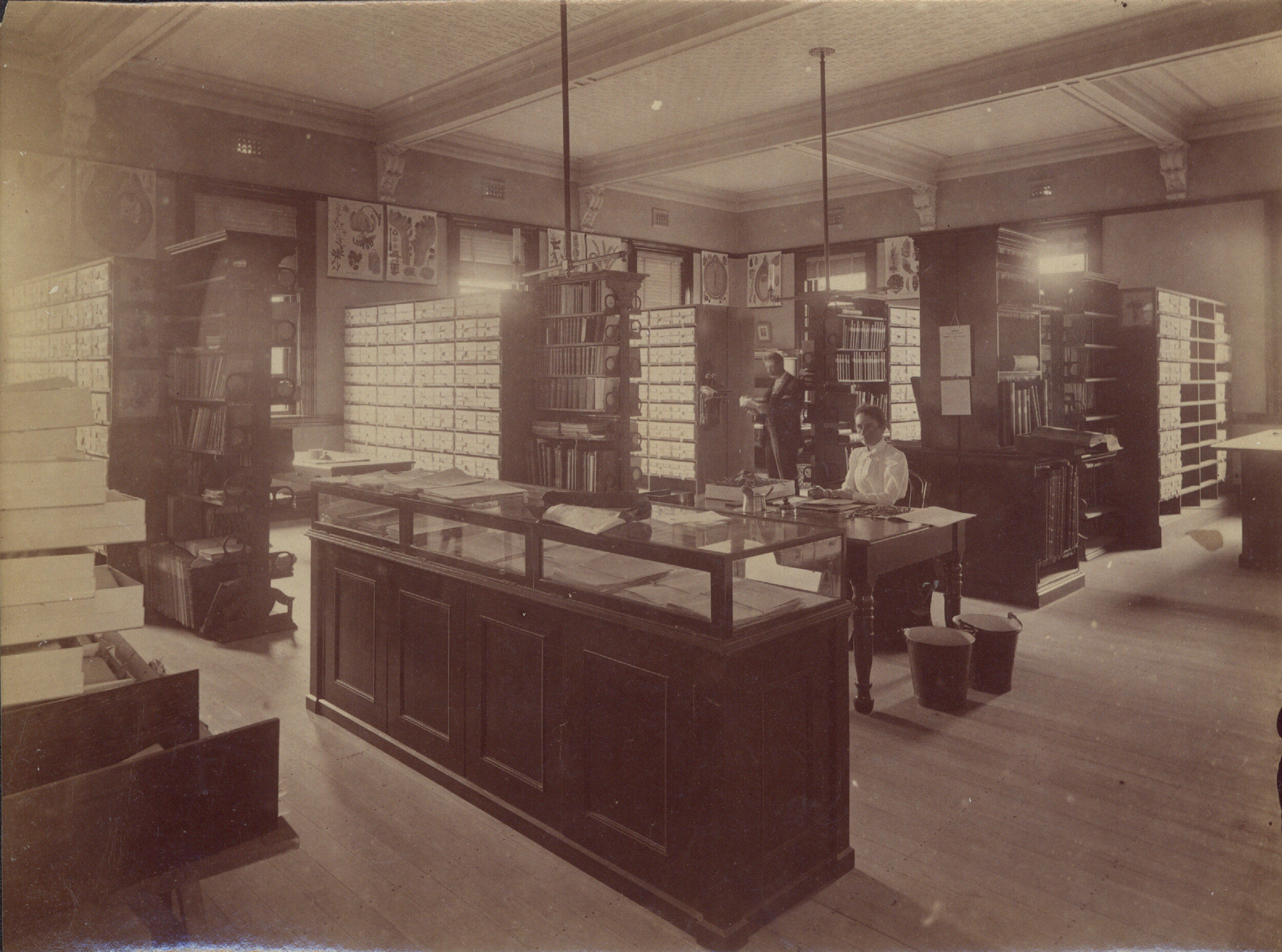

“European naturalists […] tended to collect specimens and specific facts about those specimens rather than worldview, schema of usage, or alternative ways of ordering and understanding the world. They stockpiled specimens in cabinets, put them behind glass in museums, and accumulated them in botanical gardens and herbaria, but as specimens "stripped of narrative," supporting once again the notion that "travelers never leave home, but merely extend the limits of their world by taking their concerns and apparatus for interpreting the world along with them.” (2)

James Delbourgo explains how imperialism and slavery shaped botanical collections and served as a foundation for the British Museum:

“Plant specimens returned to England on the same boats that took slaves to the Caribbean. And many of the beautiful examples that we admire today were picked and pressed by slaves.” 3

Many enslaved people in the Americas and Africa acted as collectors for European natural historians. The plants, bugs, and animal specimens they collected became the basis for natural history collections across Europe.

“Natural historians often sent detailed instructions to their European contacts in the colonies, but they relied on local knowledge to find particular specimens and to undertake the sometimes difficult or dangerous work of collecting. Enslaved Africans and indigenous peoples were sometimes paid for this work [in the form of better treatment, freedom, food, etc.], but rarely acknowledged.” (4)

“We've been so negligent in bringing these histories [of slavery and science] together. We've missed that they are in fact the same history.” -James Delbourgo

BOTANICAL GARDENS

“Botanic gardens are generally seen by the public as beautiful green enclaves planted with rare trees and flowers [but] botanic gardens had a period of intense activity in the service of Western colonial expansion. Through the exercise of sheer power as well as by their scientific expertise, they increased the comparative advantage of the Western core of nations over the rest of the world. The alliance of science, capital, and political power had systemic results that we still wrestle with today.” (5)

“European botanical gardens…were founded in the sixteenth century primarily as “physic” gardens (gardens of medicinal plants) attached to universities and hospitals to cultivate “simples” for medicine and to teach medical botany to physicians and apothecaries. By the eighteenth century, these gardens were networked with experimental colonial gardens [around the world].” (1)

“Kew [Royal Botanic Gardens] became a clearinghouse for the exchange of plant information and a depot for the interchange of plants throughout the [British] empire; it sent plants wherever it saw commercial possibilities. With one foot in the tropics of each hemisphere—with colonies in both wet and dry environments, at sea level and in the Himalayas—Britain could shuffle plants at will.” (5)

History professor Jim Endersby discusses the role Kew Gardens had in advancing the British Empire:

SOURCES

Lafuente, Antonio, and Nuria Valverde. “Chapter 8/ Linnaean Botany and Spanish Imperial Biopolitics.” Colonial Botany Science, Commerce, and Politics in the Early Modern World, by Londa Schiebinger and Claudia Swan, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016

Schiebinger, Londa. “Chapter 7/Prospecting for Drugs: European Naturalists in the West Indies .” Colonial Botany Science, Commerce, and Politics in the Early Modern World, by Londa Schiebinger and Claudia Swan, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016.

Jardine, Lisa. “Age of Exploration,” Seven Ages of Science. BBC, 2013.

Natural History Museum (UK). “Slavery and the Natural World.” Chapter 9: Transfer and exploitation of knowledge. 2008

http://www.nhm.ac.uk/files/pdfs/assets/chapter-9-transfer-of-knowledge.pdf

Brockway, Lucile H. “Science and Colonial Expansion: The Role of the British Royal Botanic Gardens.” American Ethnologist, vol. 6, no. 3, 1979, pp. 449–465. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/643776